This blog discusses the scale of the global pension funding crisis and highlights the risk to Sovereign credit ratings.

This week the main holders of Gilts refused to co-operate with the Bank of England. The post-Brexit QE stimulus relies on pension funds and insurance companies selling Gilts at attractively high prices and low yields; but this apparent benefit leaves them with surplus cash, and low interest rates which drive up the value of their liabilities.

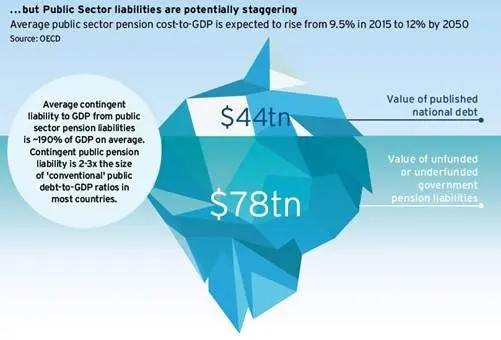

Gilt owners who are trying to hedge their liabilities have good reason to be awkward; Hymans Robertson recently estimated that the overall UK pension deficit is more than £900bn, and about two-thirds of this is in the public sector. And the problem is not specific to the UK, as the Citigroup graphic at the end of this piece shows: underfunded Government liabilities are globally worth $78trn.

Rising pension deficits are not a new issue, but the speed and scale of the recent deterioration has pushed them onto the front pages of the financial press. The core issue is low annuity rates, driven by low interest rates and demographics. People are living longer, and the birth rate is not high enough to prevent the population from aging; so the demand for pension payouts is much stronger than the supply of fresh contributions.

Corporations have made substantial contributions (close to $100bn in recent years) in an attempt to plug the gaps. But since many corporations have also been taking advantage of low rates to issue large volumes of debt, the process is becoming circular.

The numbers appear to be terrifying, and have prompted some extreme responses: some companies are offering amazingly generous transfer values to persuade DB scheme members to cash out. But the reality is more mixed. Rising deficits are the result of marking-to-market in a world of low rates, and yield curves may change significantly in the intervening decades before most of the payouts become a reality. Commercial solutions – such as annuity bulk purchase – are potentially available to corporates.

Banks have taken a relaxed view: the typical CBC* of private sector pension funds and companies with large pension deficits has been stable this year. But for the public sector, the outlook is more difficult. While it is true that normalised interest rates would make a substantial dent in most of these deficits, pension promises are a growing burden for Governments and taxpayers. In many countries they are the largest and most intractable element of the public budget deficit. If current trends continue, pension deficits will become an increasingly important factor in Sovereign credit risk.

*CBC = Credit Benchmark Consensus; a 21-category scale which is explicitly linked to probability of default estimates sourced from major banks. A CBC of [bbb+] is broadly comparable with BBB+ from S&P and Fitch or Baa1 from Moody’s.