By accident or design, Russia has weaponized energy supplies. European Governments are pledging hundreds of billions of Euros in financial aid to power generators and distributors, plus support for consumers facing massive energy price hikes. But an even larger crisis may be lurking in European energy trading, with the FT reporting sector margin requirements as high as €1trillion – vastly in excess of current sector liquidity.

Detailed consensus credit data is available on Bloomberg or via the CB Web App, covering many otherwise unrated companies. To arrange a demo of all single name and aggregate data detailed in this report, please request this by sending us an email.

Primary energy producers – oil companies, coal and uranium miners1, hydro schemes, solar and wind farms – are mainly concerned with achieving a minimum selling price – they are typically natural sellers of energy futures. Power generators can control their output provided they have access to raw energy supplies – but many do not own these outright. So the latter may hedge inputs and outputs, but need to make physical delivery. Power distributors are one step further along the power supply chain, even more vulnerable to input-output price and volume mismatches – including the risk that consumers cannot pay for usage.

Duration risk, basis risk and delivery risk are all live issues for the sector. Via exchanges and bilateral OTC deals, companies across the power supply chain hold extensive2 (up to five times the end user demand) long and short positions. Many firms have sold future output at prices that have been overtaken by war and market volatility, leaving them vulnerable to margin calls as their short positions are squeezed. For some, those short positions are covered by physical production that should materialise in the future, so their current challenge is a liquidity issue that need not become a solvency issue with help from their bankers or their governments.

But some energy generators and many energy distributors face existential risk – with potentially uncovered short sales stretching into the future which they may not be able to honour.

Putin’s decision to suspend all oil and gas supplies to Europe has put distributors in this impossible position; and they will argue that the sudden lack of physical deliverable is beyond their control, leaving them having to buy energy on the open market at any price. If their banks are understandably reluctant to provide finance, Governments face the difficult choice of acting as insurer of last resort (adding to post-Covid debt piles) or letting them collapse.

The latter has huge systemic risk implications; not just for exchanges (ICE for oil and gas, Nasdaq and EEX for electricity) but also for CCPs and their members, and even for apparently well-capitalised energy firms who have potentially insolvent counterparts.

It has been described as a “Lehman moment” for the sector, and there are parallels with the 2008 financial crisis: many of these positions will come good over time provided supplies can be found somewhere to meet the obligations, but in the meantime, there is a need for a large lifeboat.

Iberdrola subsidiary Scottish Power has proposed amortizing the necessary consumer and corporate help over multiple years – a recognition that these are exceptional circumstances. The EU is proposing a form of “power bank” where firms with windfall gains could finance those in distress until prices and volumes stabilise.

But how to identify who is a winner and who is a loser? As in 2008, the tangle of derivative deals – many undisclosed – risks contagion across the industry. Some companies may not know their true net position until they know which of their counterparts are in a position to deliver financially or physically. The complex legal relationship between holding company and operating subsidiary is a further problem – creditors may not be sure that their loans are actually backed by assets.

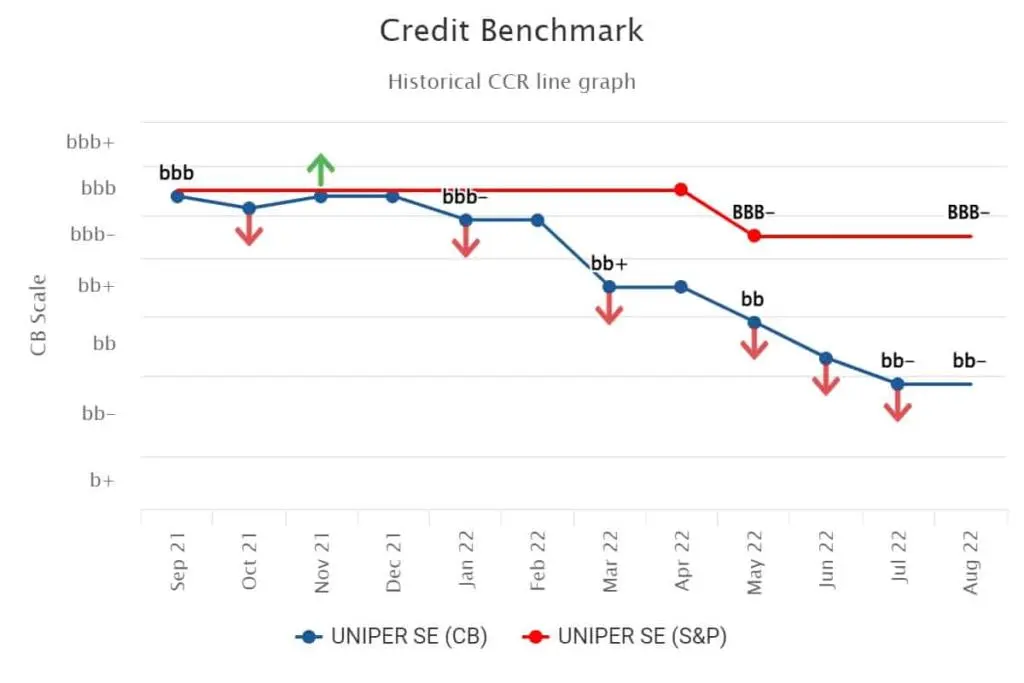

For example, figure 1 shows the credit history for Uniper.

Figure 1: Uniper Consensus Credit Rating History

From bbb last year, Uniper has declined steadily to bbb-, bb+, bb and now bb-. The long term S&P rating remains investment grade and Uniper has effectively been bailed out (and may be nationalised); but for lending banks there was no guarantee that this would happen.

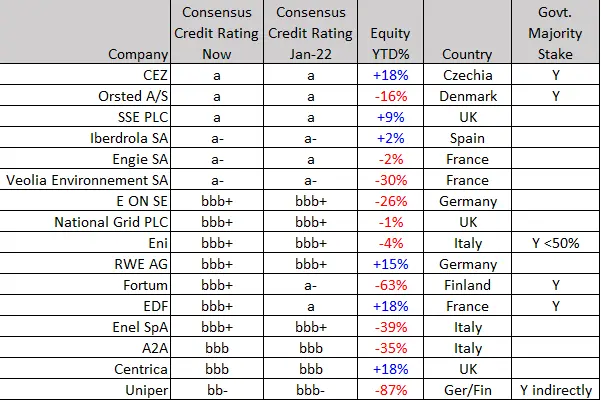

Recent share prices and consensus credit data across the sector reflect this uncertainty, with the latter sourced directly from banks facing major and critical lending decisions. Figure 2 shows current and recent consensus ratings for some of the main energy companies, along with equity price performance for the quoted firms.

Figure 2: Consensus Ratings and Equity Performance of Major European Energy Firms

Credit is generally strong and has been stable, with the exception of Engie, Fortum, EDF and Uniper – but the enormous variation in equity performance shows the challenge for investors and lenders in this sector. Engie’s gas business is not directly dependent on Russian pipelines, but they are having to compete in the open market for increasingly limited LNG supplies. EDF’s credit rating suffered due to complete suspension of their nuclear facilities for maintenance; a government bailout has rescued shareholders and covered hedging obligations pending nuclear output coming back onstream in Q4.

Uniper, Fortum, Enel, A2A, Veolia and E ON all show significant share price weakness this year; Italy and Germany are large importers of Russian gas. RWE bucks this trend due to large coal and nuclear exposure, both of which are back in favour to fill the gap left by the Russian supply squeeze. Iberdrola and its subsidiaries are heavily focused on renewables; their shares and credit rating have been stable.

Clear double winners may emerge – those with little exposure to Russian fossil fuel supplies and windfall profits from price spikes, either due to limited hedging of output or effective hedging of inputs. But the losers will include those that over-hedged and now face a price and liquidity squeeze. If counterparty risk becomes a problem, the equity and credit picture could change; and this sector has a large number of smaller firms, many of them very exposed at the moment and generally classed as non-investment grade.

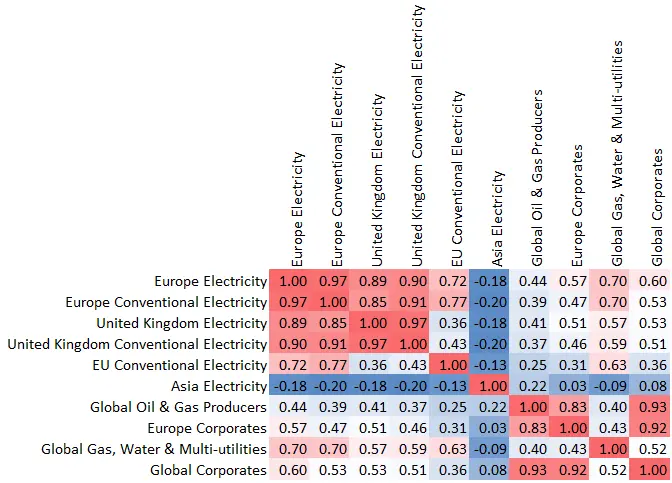

Consensus credit data is sourced directly from major global banks – it covers more than 100 European energy companies, many of them unrated, or private, or subsidiaries of the holding companies; the latter show a remarkable variation in ratings. Figure 3 shows the correlations between the European Electricity aggregate and other major aggregates (these are a small sample from a full set of 1000+ aggregates covering multiple geographies and sectors).

Figure 3: European Electricity correlations, 2020-2022

European electrical companies show some striking divergences in credit risk behaviour; UK Conventional Electricity default risks are highly correlated (+0.90) with the main Europe Electricity aggregate, but only +0.43 with the EU Conventional Electricity companies. The European sector is – not surprisingly – completely independent of Asia, with low negative correlations, and only modestly correlated (+0.25 to +0.44) with Global Oil & Gas Producers. Correlations with Global Utilities are stronger (+0.57 to +0.70), while correlations with European and Global Corporates are almost identical.

Single name consensus credit data covering 30,000 corporates and financials is now available on Bloomberg for direct comparison with equity and bond prices. Single name data and aggregate time series are available in the Credit Benchmark Web App or in csv file format. Contact [email protected] for more information.

[1] Insight – Uranium: Kazakhstan Effect May Be Transitory, EU Policy May Be Critical – Jan-22

[2] FT estimate 11th September 2022.